Elementary particles

Think about anything that you used today: a book, your phone, or even your hand- all of these are made up of molecules, which in turn are composed of atoms. The arrangement of atoms in specific ways gives materials and matter their unique the properties. This is why you can distinguish between a book and your phone. Chemists study these interactions of atoms by considering protons, electrons and neutrons.

Particle physics takes this understanding a step further by exploring what protons or neutrons themselves are made of and examining how the smallest particles interact with one another. This field addresses questions that chemistry cannot fully explain, such as the the process powering the sun. For example, it is through particle physics that we understand why the sun provides energy and why you can read these words.

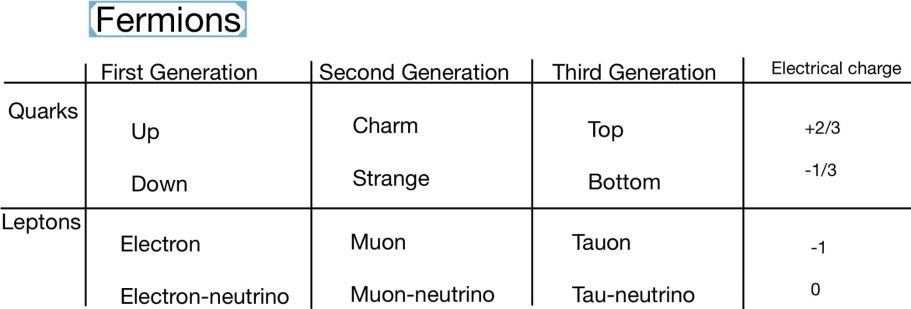

Elementary particles are categorized into two main groups: fermions, the generations of matter, and bosons, the force carriers. Fermions are further divided into quarks and leptons.

All Fermions have antiparticles with opposite charge but the same rest mass. When antimatter interacts with matter, they annihilate each other, releasing energy.

Quarks

Quarks cannot (as far as physicists currently understand) be divided any further and represent the most basic component of matter. The most common quarks in our everyday life are up (u) and down (d) quarks, which are classified as the first generation of quarks.

A proton is made up of two up quarks and one down quark (p=u+u+d), while a neutron consists of two down quarks and one up quark (n=u+d+d). Particles like neutrons or protons are known as baryons because they are composed of three quarks.

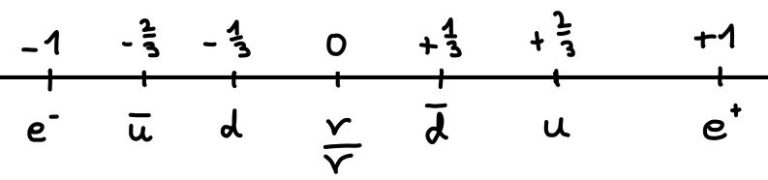

Quarks carry electric charge. The up quark has the charge of +2/3e and down quark -1/3e. Using this, we can calculate the charge of the baryons like the proton and neutron:

· p = 2/3+2/3-1/3= +1

· n =-1/3-1/3+2/3= 0

However, four additional quarks have been discovered in particle accelerators like the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN.

The strange (s) quarks, often referred to as the heavier cousin of the down quark (also with electrical charge of -1/3e), and the charm (c) quark, referred to as heavier cousin of the up quark (also with an electrical charge of +2/3e), build together the second generation of quarks. They can both build various new types of mesons (consisting of an antiquark and a quark) and baryons (consisting of three quarks).

The third generation of quarks include even heavier counterparts: the bottom quark (b), a heavier cousin of the down quark, with an electrical charge of -1/3e; and the top (t) quark, a heavier cousin of the up quark, with an electrical charge of +2/3e.

Unlike the first generation, the second and third generation are rare in our environment because nature always favors the most stable state with the lowest energy and mass. Heavier quarks tend to decay into lighter ones, emitting an electron or positron along with a neutrino or anti-neutrino.

Leptons

The other group of fermions is leptons, which typically have an electrical charge of -, except for neutrinos, which have no electrical charge.

The most well-known lepton is the electron, which belongs to the first generation with its neutrino, the electron neutrino. The electron has relatively little mass and its mass is often neglected when compared to the proton or neutron. Electrons are responsible for most chemical reactions and are products of the beta decay. Moreover, they play a vital role in fueling us with energy. By being a product in the fusion of the sun and interacting with their antiparticle, the positron, they decay into photons (energy).

The second generation includes the muon and its neutrino. The muon is approximately 200 times heavier than the electron, which makes it far less common. It decays rapidly into lighter particles.

The third generation of leptons consists of the tauon and its neutrino. The tauon is about 3500 heavier than the electron and behaves similarly to the muon.

Neutrinos have become more and more interesting in recent years, as physicists believe that they may hold answers to fundamental questions, such as the number of dimensions or the Big Bang. Neutrinos are nearly massless, carry no electrical charge, and can pass through almost anything- including you right now. In fact, about 400 billion neutrinos from the sun pass through each one of us per second. Additionally, radioactive materials in the earths crust emit neutrinos, 50 billion of them pass through us every second. However, detecting neutrinos is extremely challenging. A single neutrino could travel through a light year of lead without interacting with anything. Despite this, advanced detectors and the immense number of neutrinos increases the probability of interaction- such as with an electron- which made it possible to detect them.

Bosons and fundamental forces

The electromagnetic force and the photon

You, I, and everything we see around us is hold together by the electromagnetic force. The reason we do not fall through the ground is that the electromagnetic force holds the electrons in atomic paths around the nucleus and binds molecules together. This force operates under the principle “like charges repel and opposite charges attract.” Electrons carry a negative electrical charge and protons a positive one (u+u+d=+1), causing them to attract each other. The strength of this attraction can be calculated using the law of Coloumb:

F=(1/4×π×ε)q₁q₂/r²

Here, F is the magnitude of the electromagnetic force between the charges q₁ and q₂, which is directly proportional to the product of the magnitudes of their charges and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

Below is the electrical charge of up and down quarks, their antiparticles (with a line over the letter) and the electron, and its antiparticle, the positron.

Interactions between electrically charged particles occur through the emission and absorption of virtual photons, the bosons of the electromagnetic force. Imagine two people in space playing with a ball. When one person throws the ball and passes momentum on it, they feel a recoil. When the other person receives the momentum of the ball by catching it, they also experience a recoil. This exchange represents a repulsive force. In nature, this process happens when electrons exchange virtual photons, leading to their repulsion. Many other particles exchange virtual photons in this way, and their tendency to interact via this mechanism is called the electric charge.

Photons are emitted when electrically charged particles move, causing changes in their electromagnetic field. The photon has no mass or charge and is essentially an electromagnetic wave traveling through space at a speed of 299 792 458 m/s. Due to the wave-particle-dualism photons can be described both as particles of electromagnetic waves and as carriers of light and energy. Photons possess discrete energy levels which cannot be divided. This energy is stored in the oscillating electric and magnetic fields. Maxwells equations describe the nature of the movement of photons.

The strong force and the gluon

After physicist discovered that the nucleus of an atom consists of protons and neutrons, they faced a paradox: since protons carry a positive electrical charge (u+u+d=+1) and we know that positive charges repel each other (as described by Coloumbs Law), how can the nucleus, where several protons are right next to each other, remain stable?

To solve this paradox, we need to look at the quarks inside the proton rather than the proton as a whole. It turns out that quarks in protons are not only electrically charged, but also possess a property known as strong charge. This strong charge comes in three varieties, referred to as red, blue and green (this has nothing to do with the actual colors). Unlike the case of electromagnetic charges, quarks with different colors (eg. red and green) attract each other, while like colors repel. A proton with one red, one blue, and one green quark remains stable because these colors combine to form a “white” (neutral) color charge. However, if a fourth color were introduced, it would be repelled by one of the existing colors.

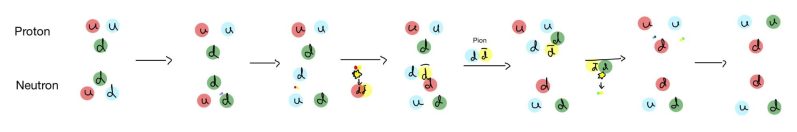

The boson of the strong force is called the gluon. The strong force arises from the emission and absorption of gluons by quarks. For instance, in a proton (which consists of two up quarks and one down quark), gluons are continuously exchanged between the three quarks. This exchange causes the quarks color charges to change dynamically while maintaining an overall neutral charge for the proton. in. Gluons, while transferring their color charge, can form particles called pions due to quantum effects. A pion is a type of meson, composed of one quark and one antiquark. These pions act as exchange particles for the strong force between protons and neutrons or protons and protons. You can imagine them flying between nucleons and therefore holding them together.

The following illustrates the interaction of the colored quarks of a proton and a neutron which change their color via gluons. They stay together through gluons and their ability to form pions for a very short period of time.

This process explains our paradox: protons inside a nucleus are “glued” together by the strong force, which operates with principles of attraction and repulsion similar to the electromagnetic force. At larger distances, though, the strong force weakens, while the electromagnetic force becomes more dominant. This is why nuclei with too many nucleons, such as in uranium, becomes unstable. In these cases, the repulsion between protons due to the electromagnetic force outweighs the attraction provided by the strong force, leading to instability and radioactive decay. Atoms like uranium are not stable anymore because their protons feel a bigger repulsion (electromagnetic) than attraction (strong force).

The weak force and the W and Z boson

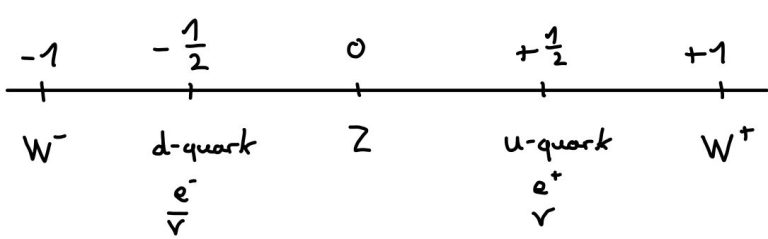

The weak force is responsible for processes such as the β-decay, which occurs in the sun during fusions. The weal force is mediated by three bosons: the W-minus (negative electrical charge), W-plus (positive electrical charge) and Z (no electrical charge). Many elementary particles possess a weak charge which is shown for a few particles in the following:

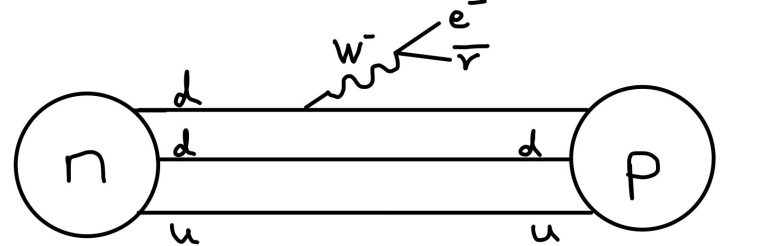

The electrical charge of the W bosons plays a key role in beta decay by transferring charge away from the source. In beta-minus decay, a neutron (neutral) turns into a proton (positive) while emitting a W-minus. The W-minus boson subsequently decays into an electron and an anti-electron-neutrino.

The W-plus boson occurs at the β-plus decay where a proton transforms into a neutron while emitting a W-plus.

However, this brings us to a paradox: the mass of the W boson is approximately 80 times greater than that of a proton or neutron. How can such a massive particle exist in these processes without violating conservation of energy?

The explanation lies in the quantum world, more specifically in Heisenbergs Uncertainty principle, which allows the W boson to ‘borrow’ energy for an extremely short period of time (so short that ight could only travel 1/10 of the length of a proton in that duration) before it decays (therefore the weak force has a short-range nature and is called weak).

Gravity (and the graviton?)

Gravity is likely the most familiar force to us. While the strength of gravity between individual particles is extraordinarily small and often negligible in particle physics, it becomes significant over large distances and keeps heavy objects, like the earth, in orbit around the sun.

Isaac Newton developed a theory of gravity that remains highly applicable in our daily lives. However, he did account the finite speed if light. Later, Albert Einstein proposed a completely new theory of gravity: gravity is not a force in the traditional sense but rather the result of the curvature of space-time. For example, an observer outside the solar system would not see a direct force pulling earth toward the sin. Instead, they would observe that space around earth is curved by the massive sun, so that empty space is pushing the earth circling around the sun. Einstein explained that when you sit in your chair, it is not a gravitational pull that holds you down but the curvature of space-time caused by earths mass, which pushes you into the chair.

To uniform general relativity with the standard model of particles physics, scientists hypothesize the existence of a particle called the graviton, which could act as the boson mediating gravitational interactions.

A universe with gravitons would look like a smooth surface and space-time, introduced by Einsteins theory of relativity, would be surrounded by a cloud of trillions of tiny graviton particles.

©Copyright. All rights reserved.

Wir benötigen Ihre Zustimmung zum Laden der Übersetzungen

Wir nutzen einen Drittanbieter-Service, um den Inhalt der Website zu übersetzen, der möglicherweise Daten über Ihre Aktivitäten sammelt. Bitte überprüfen Sie die Details in der Datenschutzerklärung und akzeptieren Sie den Dienst, um die Übersetzungen zu sehen.