Reality: an illusion or the truth?

Albert Einstein once said „ Reality is merely an illusion, although a very persistent one “- he really was a deep thinker!

Dimensions: A question of perception

We assume that we exist in a three-dimensional world (excluding poor old time for now) – but how do you know our perception reflects reality?

At first glance, you might raise an eyebrow and argue that I can only move up, down and sideways. But does this truly limit the existence of other dimensions, or does is merely reveal the constraints of our physical and cognitive abilities?

A journey to Flatland

Let me show you what I mean with a thought experiment:

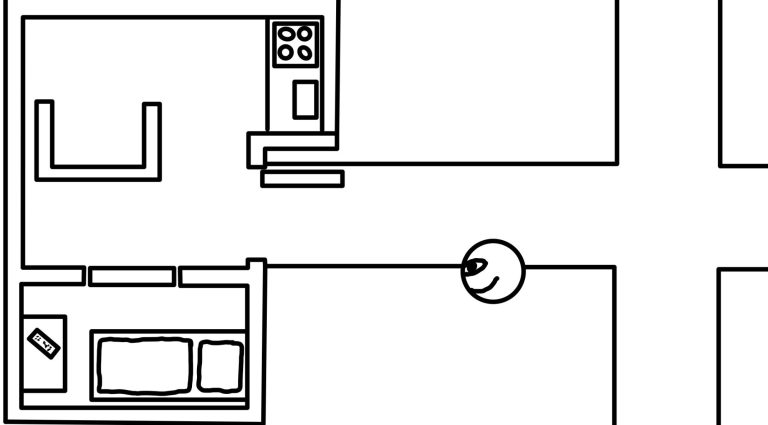

Imagine a creature named Mike who lives in Flatland.

Flatland is not my next vacation spot but a two-dimensional world, much like the drawings I proudly made at the age of five – yes, I was a true artist. Mike is cognitively not able to understand three-dimensional objects lake balls, dice, or – heaven forbid- smartphones!

In Flatland, everything has a length and with but no height.

Mikes strange encounter

One day, Mike leaves his house and sees a circle that keeps growing and shrinking. Confused yet curious, he developes equations to describe the velocity, frequency, and other properties of the circle.

But equations are not enough for Mike – he is a philosopher at heart.

Where do these circles come from?

Where are they going?

And why do they exist?!

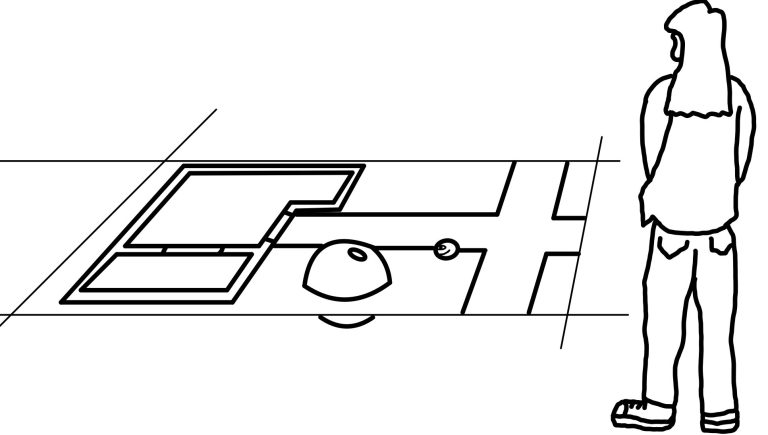

Enter Grace, the three- dimensional observer

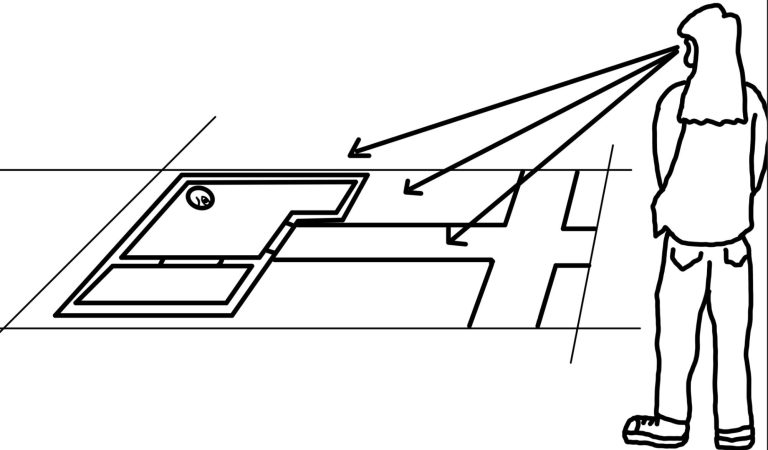

Now let us introduce Grace, who lives in our three-dimensional world. Grace sees the whole picture – literally- and observes Mike in his two-dimensional Flatland. She knows the circles Mike sees is the cross-section of a bouncing ball jumping up and down through Flatland. Grace understands that Mike sees the cross-section of the ball, but his two-dimensional brain is cognitively not able to comprehend the three-dimensional ball.

For Mike, Grace would seem like a supernatural, godlike being because she can observe him wherever he is - even if he hides behind walls – creepy, right? But Grace is not peeping through walls; she is just using a dimension that Mike cannot perceive.

Graces own curiosities

Grace is just as clueless as Mike when it comes to the mysteries of her own world. She can calculate the trajectory of planets or the behavior of light, but she does not know where the universe came from or why things are the way they are. She is like a cat chasing a laser pointer – fascinated but fundamentally limited.

If we extend Mike and Grace’s story to imagine a four-dimensional creature observing Grace, we get a humbling lesson.

Fourth dimension?

Just as Grace (representing humanity) can observe all points on Flatland, a four-dimensional being could see every point in our world, wherever we are – yes, even when you are hiding under a blanket, pretending the world does not exist.

Mike can write equations for the circle but could not understand the reality of this circle.

Similarly, we can observe the universe and develop equations but might never understand reality with our cognitive abilities. It is like trying to capture a mountain in a photograph – you get the shape, but the depth is lost.

The nature of knowledge

We can not know reality with absolute certainty; we can only make educated guesses with varying probabilities of being correct. Everything has a chance of being false – even the most trusted theories.

The key to growth and success is keeping an open mind, admitting when you are wrong, and embracing perspectives that challenge your own.

Quantum mechanics: A blurry reality

Quantum mechanics teaches us that reality does not exist in a definite and certain state independent of observations. This does not mean we create reality by observing but rather that observation reveals one version of it that is unique to the observer.

Take quantum tunneling, for example. It describes how a particle can be at a place it „should not “be, defying classical logic – those sneaky particles!

Or Heisenberg ‘s uncertainty principle, which says we cannot know both the position and momentum of a particle with absolute precision.

And, of course, Schrödinger’s cat reminds us that reality can exist in a blurry superposition until we see it.

Reality is not something „out there “, existing independent of us. It takes form through our intersections and observations – like when you see your favorite plate fall and break. Our observation of an event gives it meaning.

The philosophical debate: Aristotle and Plato

The question of absolute knowledge is as old as philosophy itself. To the ladybug on my keyboard, it might seem as towering as Mount Everest. The ancient Greeks, Aristotle and Plato, had opposing views on this.

Aristotle considered himself as an empiricist, arguing that you can gain knowledge from this world because everything changes, and we are able to make observations through our senses.

Plato, on the other hand, considered himself a rationalist, arguing that you can not gain knowledge from this world as everything constantly changes. For him, reality is like shadows on a cave wall – mere reflections of a deeper truth.

Is reality a simulation?

In modern days, we have taken the debate about reality to a new extreme with the simulation theory.

How do you know the world around you is real?

What if everyone you know is just part of an elaborate illusion designed to keep you believing in this version of reality?

Reality, for us, is what we can perceive and make sense of with our brains. That does not mean it is the ultimate truth?

©Copyright. All rights reserved.

Wir benötigen Ihre Zustimmung zum Laden der Übersetzungen

Wir nutzen einen Drittanbieter-Service, um den Inhalt der Website zu übersetzen, der möglicherweise Daten über Ihre Aktivitäten sammelt. Bitte überprüfen Sie die Details in der Datenschutzerklärung und akzeptieren Sie den Dienst, um die Übersetzungen zu sehen.